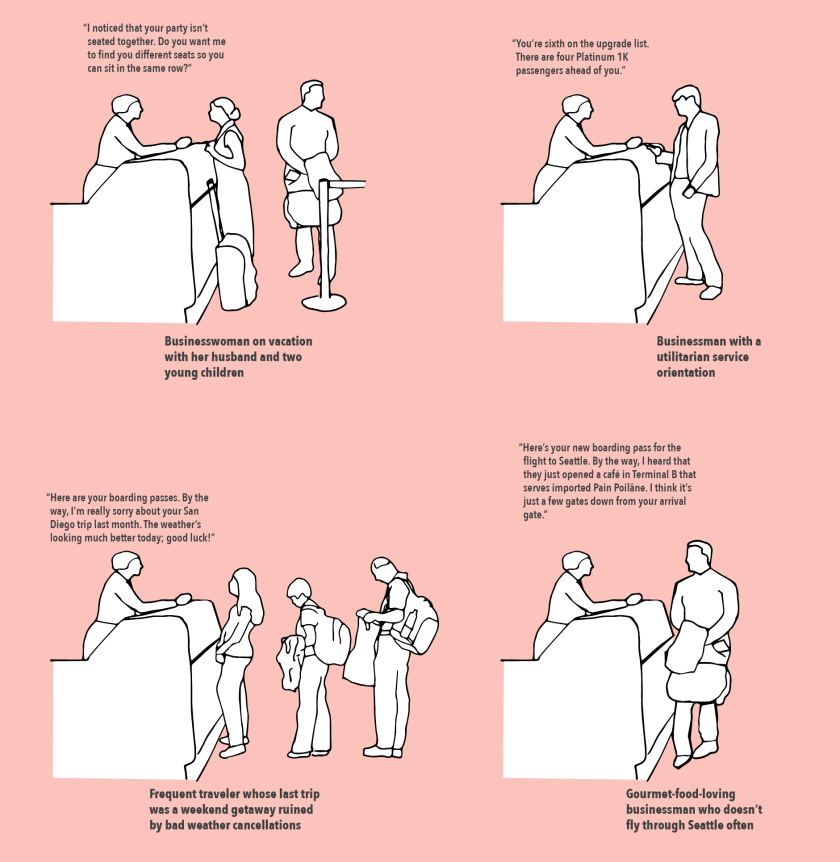

What’s the best illustration style for storyboards?

Lately, I’ve been struggling with how to depict service design scenarios, so that I can online-test them. I started by writing each scenario from the perspective of the customer, as well as the employee, then drew rough draft story boards for each:

Scenario 1, customer perspective:

Whenever she’s at Target, Ann checks to see if the Cascadian Farm Cinnamon Raisin Granola is on sale. Whenever it is, she buys one or two boxes. It’s her favorite cereal, but she feels that at the regular price it’s too expensive for her to justify as an everyday purchase.

This afternoon, Ann is at Target browsing for clothing. She’s looking at a rack of tights and socks when a Target employee walks by. He stops and says to Ann, “Hey there – just wanted to let you know that we are having a sale on Cascadian Farm stuff, like cereal and granola bars!”

Ann is happy to hear this, and when she’s done looking at clothing, she goes over to the grocery section to get a box of the cereal.

Scenario 1, employee perspective:

Jay is an employee at Target. Today he is tidying up the displays in the clothing department. He carries with him a mobile device that was given to him by the Target manager – the device has information that he can give to customers to help them have a better shopping experience.

He glances at the mobile device as he walks by the socks display. It shows that a customer who is currently browsing the socks display is a big fan and frequent buyer of Cascadian Farm Cinnamon Raisin Granola, but only when it is on sale. It prompts him to mention the current sale to her.

Jay says to the customer, “Hey there – just wanted to let you know that we are having a sale on Cascadian Farm stuff, like cereal and granola bars!” The customer smiles back.

What I’m struggling with is refining the drawings for my online test. I don’t want to make them too “finished” or “polished,” because to do so would not invite criticism as readily, and I want honest criticism of my concepts. (Furthermore, I want to de-emphasize the aesthetics here, and instead focus people’s attention on the service concepts.)

My first attempt at a more refined storyboard is all wrong:

I think they’re too busy and don’t fully emphasize the service.

What direction should I go in?

**Update: A classmate suggested a gray background to increase the attention on the characters: